Quick Take:

What happens when moral inability is treated as a permanent condition that only selective mercy can cure?

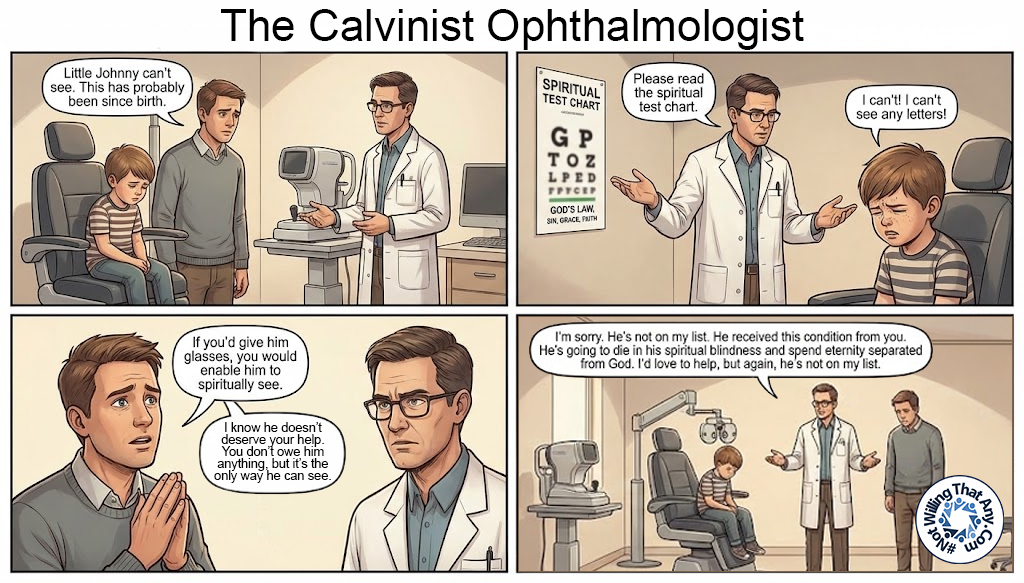

This illustration presses that question by placing Calvinist theology into a medical setting, where blindness is real, inherited, and fatal if untreated. The ophthalmologist does not deny the child’s blindness or the need for sight, but refuses to give what would heal, not because the cure is unavailable, but because the child is “not on the list.” The image forces the viewer to ask whether this portrayal matches Calvinism’s own claims about inability, election, and responsibility, and if so, whether that outcome reflects justice, love, and sincerity as we instinctively understand them.

Is it an accurate picture of Calvinism?

This image is not mocking Calvinism or questioning the seriousness of sin. It is a good faith attempt to visualize core Calvinist claims about inherited inability, selective grace, and divine choice. Like all illustrations, it simplifies, but it does so to make abstract theology concrete, so its moral implications can be examined rather than hidden behind technical language.

Total Depravity and Inherited Condition

The child’s blindness from birth directly reflects Calvinism’s doctrine of total depravity. Humanity inherits a corrupted nature through Adam and is unable to see, desire, or respond to God apart from divine action. Passages such as Ephesians 2:1 and Romans 3:11 are often used to support this idea. The illustration faithfully represents this by making the blindness real, complete, and not self-chosen by the child.

Unconditional Election and the Closed List

The doctor’s repeated reference to “my list” corresponds to unconditional election. The child is not healed because he is not chosen, not because healing is impossible or undeserved. This aligns with Romans 9:15–18, where mercy is granted according to God’s will alone. The illustration accurately shows that the deciding factor is not need, sincerity, or request, but prior selection.

Irresistible Grace and Withheld Enablement

The glasses represent enabling grace. Once given, sight would follow immediately. The doctor does not offer partial sight or an opportunity to see; the cure itself guarantees the outcome. This mirrors irresistible grace, where regeneration precedes faith and ensures response. The parent’s plea highlights the tension: if enablement guarantees sight, and the doctor alone controls it, responsibility shifts away from the child entirely.

The final panel confronts the hardest implication. The child remains blind due to exclusion, and the consequence is eternal separation. Calvinist theology often affirms that God is just in this outcome, since no one deserves mercy. The illustration does not deny that claim. It simply asks the viewer to look at it without abstraction and decide whether this is a justice they can affirm when fully visualized.

If this illustration accurately reflects Calvinist theology as it understands itself, the remaining question is not whether it is precise, but whether it is morally and theologically satisfying once seen rather than merely stated.