Quick Take:

What does “free will” really mean?

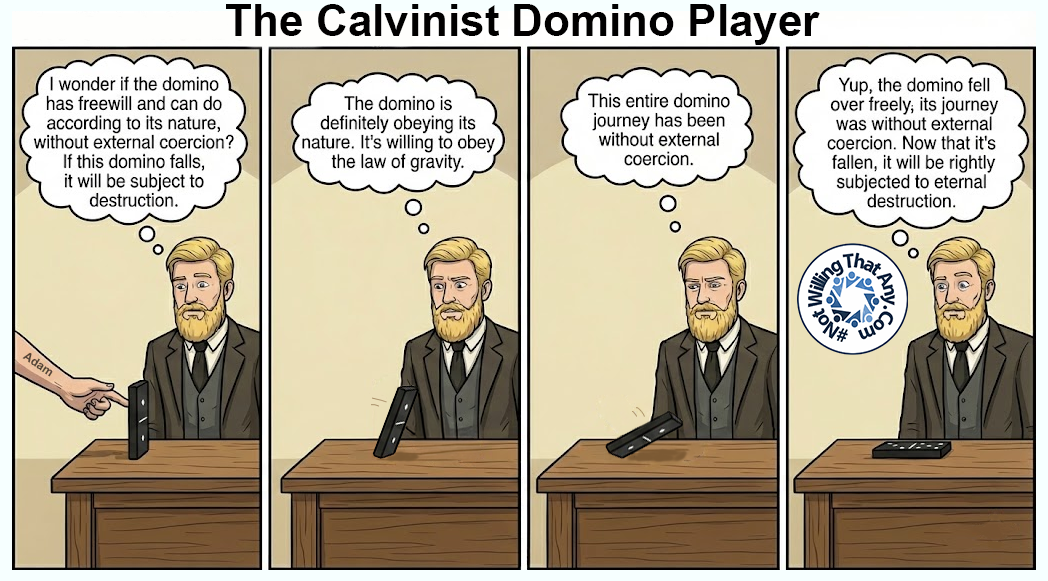

This illustration presses on a common compatibilist definition of free will: acting according to one’s nature without external coercion. The domino “falls freely” because it obeys its nature and is not externally forced beyond what already determines it. Yet once the domino falls, it is judged and destroyed for doing exactly what it was always going to do. The image asks whether redefining freedom this way truly preserves moral responsibility, or whether it simply relabels inevitability as choice.

Is it an accurate picture of Calvinism?

This illustration is not claiming that Calvinists believe humans are literal objects or that moral agents are the same as dominos. Instead, it takes a commonly stated compatibilist definition of free will seriously and applies it consistently. The goal is not mockery, but clarity: to ask whether the definition itself can bear the moral weight it is asked to carry when consequences are eternal.

Total Depravity and Acting According to Nature

In Calvinist theology, humans act freely when they act according to their fallen nature. Passages such as Romans 8:7–8 and John 6:44 are often used to argue that sinners cannot desire God apart from divine intervention. The domino mirrors this idea by acting entirely in line with its “nature.” It falls because falling is what it does. The illustration faithfully reflects the claim that freedom does not require the ability to do otherwise, only the ability to act consistently with one’s nature.

Compatibilist Freedom Without External Coercion

Compatibilism emphasizes the absence of external coercion. The domino is not pushed mid-fall; it simply obeys gravity. Likewise, Calvinism often argues that God’s decree does not coerce the will but ensures that people freely choose what they most desire (Proverbs 16:9; Acts 2:23). The image intentionally highlights how “no external coercion” can still coexist with complete inevitability.

Moral Responsibility and Just Punishment

In the final panel, the domino is judged and destroyed for falling freely. This parallels the Calvinist claim that people are justly condemned for sins they willingly commit, even though their desires and actions were foreordained (Romans 9:19–23). The illustration asks whether moral responsibility remains meaningful if the outcome was fixed and unavoidable from the start.

The question it leaves the viewer with is not whether this is an accurate picture of compatibilist freedom, but whether this picture of freedom is one that makes moral and relational sense when fully visualized.