Quick Take:

What do you do with the parts of your theology that feel hardest to say out loud?

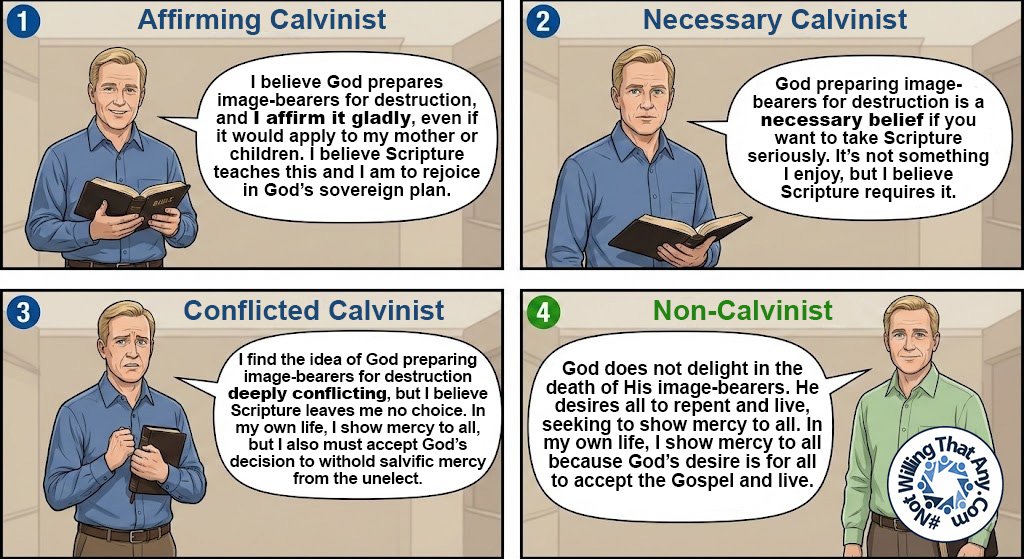

This image lays four responses side by side and quietly exposes the tension many Calvinists feel but handle differently. Some affirm God’s preparation of image bearers for destruction without hesitation, others accept it as a necessary conclusion even if it brings no joy, and others live with a deep internal conflict while still submitting to what they believe Scripture demands. By contrast, the non Calvinist response frames God’s character around sincere mercy and desire for all to live, aligning belief, emotion, and practice in one direction. The contrast is not about intelligence or seriousness with Scripture but about whether a theological system asks you to affirm, endure, or resolve the moral weight of its conclusions.

Is it an accurate picture of Calvinism?

To speak accurately about Calvinism, you have to begin with its internal moral logic, not with caricature or emotional reaction. Calvinism is not merely a set of doctrines about salvation mechanics but a posture toward God’s authority. At its core is the conviction that whatever God decrees is not only right but worthy of trust, submission, and ultimately praise, even when His purposes are difficult or unsettling to human sensibilities. Any honest portrayal of Calvinism must therefore take seriously its insistence that God’s sovereign will defines goodness rather than being evaluated by human moral intuition (Isaiah 55:8–9, Romans 9:20–21).

Divine Sovereignty:

The illustration accurately reflects Calvinism by centering everything on God’s sovereign decision. Panels 1 through 3 all assume that God actively prepares some image bearers for destruction, a conclusion Calvinists commonly ground in Romans 9:22, Proverbs 16:4, and Ephesians 1:11. The difference between the panels is not doctrinal content but emotional and moral response to that content. This captures Calvinism well because the doctrine itself does not soften the claim. God does not merely permit outcomes; He ordains them according to His will.

Unconditional Election and Reprobation:

The image reflects the Calvinist framework that election is unconditional and not based on foreseen faith or response (Romans 9:11–13, John 6:37). Importantly, the illustration also reflects the often acknowledged but less publicly emphasized counterpart: passing over or preparing others for destruction. Panel 2’s language of necessity mirrors common Calvinist appeals to “what Scripture requires,” even when the conclusion is emotionally undesirable. This accurately mirrors how many Calvinists speak about reprobation as an unavoidable inference rather than a celebrated doctrine.

Moral Alignment With God’s Will:

Panel 1 is especially accurate because Calvinism teaches that disagreement with God’s decrees is not morally neutral. God’s will is not merely something to endure but something to affirm as righteous and good (Psalm 115:3, Daniel 4:35). To judge God’s actions as troubling or morally difficult is, within Calvinism, to place human judgment above divine wisdom. The illustration captures this by showing that full consistency requires not only acceptance but rejoicing in God’s sovereign plan, however severe its implications.

Human Response and Submission:

Panel 3 reflects a common lived tension among Calvinists who feel the moral weight of the doctrine but believe faithfulness requires submission despite inner conflict. This is an accurate pastoral reality, yet the illustration rightly exposes the instability of that position. Calvinism does not ultimately permit sustained moral disagreement with God. Grief may be acknowledged, but moral resistance must be repented of. Job is silenced, not vindicated in protest (Job 40:1–5). Paul does not resolve Romans 9 by softening its claims but by rebuking the questioner (Romans 9:19–21).

This leads to the uncomfortable but necessary conclusion the illustration presses. Within Calvinism, only the first panel is fully coherent. If God’s will defines righteousness, then praising His sovereign choice is not optional. Reluctant acceptance still implies a higher moral standard by which God is being measured. Uneasy submission still suggests that mercy, if it were up to us, would look different. Calvinism cannot finally allow that posture without calling it sinful. To affirm God rightly is to affirm Him gladly.

And that raises the quiet question the illustration leaves hanging. If Panel 1 is the only position that fully aligns with Calvinist theology, is that a picture of God’s character you can embrace? And if not, is it worth considering whether Panel 4 better reflects the God revealed in Scripture, the one who does not delight in the death of the wicked but desires all to repent and live (Ezekiel 18:23, 33:11, 1 Timothy 2:4, 2 Peter 3:9)?