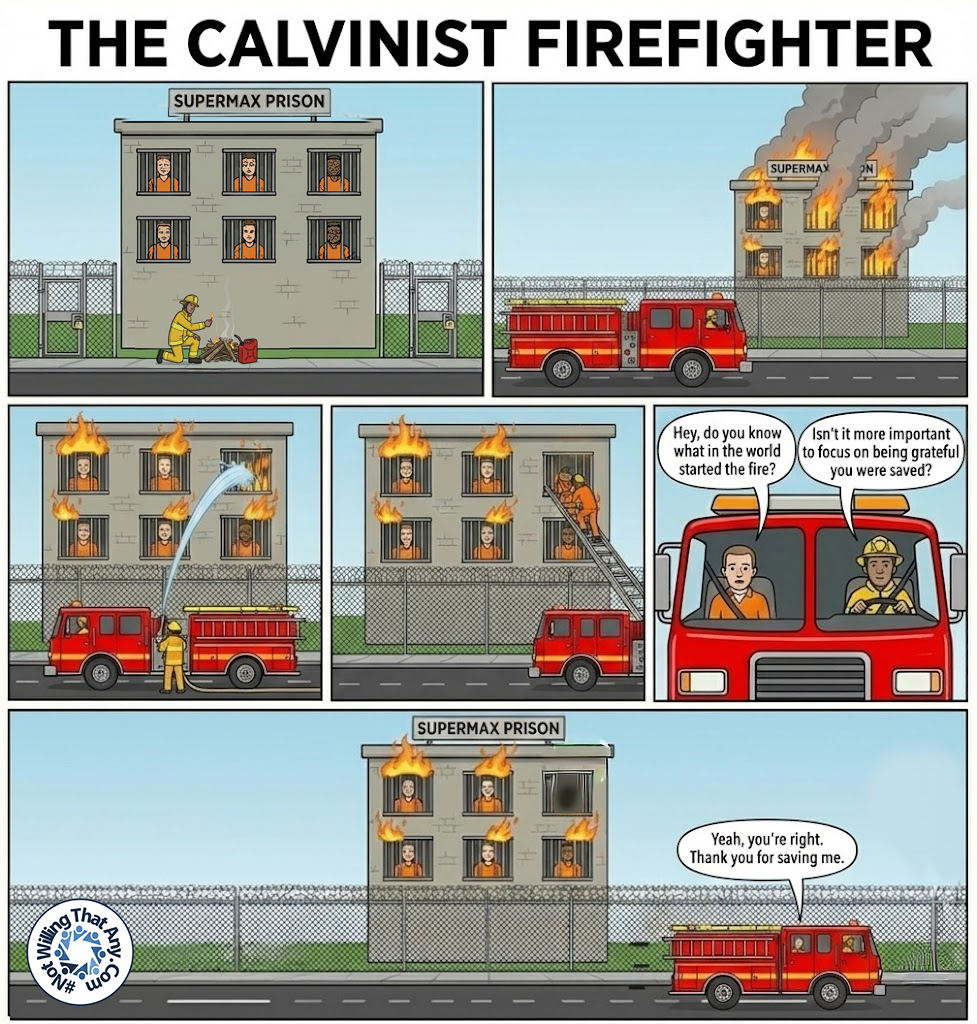

Quick Take:

This illustration critiques a framework in which rescue is emphasized while questions of cause, responsibility, and remaining danger are sidelined. The firefighter saves some prisoners from a burning building, yet leaves the fire itself largely unaddressed, and discourages questions about how it started or who remains inside. The exchange highlights a tension between gratitude for salvation and the biblical concern for truth, justice, and the fate of others still in peril. Scripture consistently calls for both thankfulness for deliverance and honest reckoning with causes and consequences (Psalm 107:2; Proverbs 4:23). God’s heart is revealed not only in saving individuals, but in confronting evil, exposing darkness, and desiring that none remain in danger or judgment (Ezekiel 18:23; 2 Peter 3:9). By redirecting attention away from the ongoing fire, the illustration raises the question of whether a theology that discourages such inquiry aligns with God’s revealed concern for truth, responsibility, and the full scope of redemption (John 3:19–21; Isaiah 1:16–17).

Is it an accurate picture of Calvinism?

What is depicted here is meant to be understood as an internally consistent picture of Calvinist soteriology, assuming its core doctrines as givens rather than arguing for them. The illustration is not asking whether these doctrines are correct, but whether this is what they entail when applied coherently.

Total Depravity: The prisoners are shown as completely unable to rescue themselves or meaningfully alter their condition. Deliverance must come entirely from outside intervention, not from initiative or cooperation within (Romans 3:10–12; Ephesians 2:1).

Unconditional Election: The firefighter’s decision to rescue is selective and not based on any action, response, or condition within the prisoners themselves. The determining factor lies solely in the will of the rescuer (Romans 9:11–16).

Particular Redemption: The rescue is effective only for those the firefighter intentionally saves. The act of deliverance is successful and complete, but limited in scope by design rather than ability (John 10:11; Matthew 1:21).

Irresistible Grace: Those who are rescued are acted upon decisively and unilaterally. They do not resist the rescue, nor do they contribute to it; the action succeeds because it is effectual (John 6:37; John 6:44).

Monergistic Salvation: Salvation is accomplished entirely by the rescuer. The prisoners contribute nothing to the act itself, functioning only as passive recipients of deliverance (Ephesians 2:4–5; Titus 3:5).

Proper Response: The appropriate posture of the rescued is framed as gratitude rather than inquiry. Questions about cause, scope, or fairness are treated as secondary to thankfulness for being saved (Romans 9:20–21).

Divine Priority: The focus remains on the certainty and success of individual rescue rather than on concern for those left behind. The illustration reflects a theology that prioritizes effectual salvation over universal intent (John 17:9).

Sovereign Will: The rescuer’s decisions are final, unquestioned, and determinative. His will functions as the ultimate explanation for who is saved and who is not (Daniel 4:35; Romans 9:18).

Taken together, the illustration does not claim that Calvinism is cruel or insincere. It aims to show what Calvinist theology looks like when its doctrines are applied consistently in narrative form.

That leaves the question unchanged: if this is an accurate picture of Calvinist theology, is it one you can accept?